Christopher Priest, towering writer of a clever, multifaceted, poignant science fiction passed away this week-end. My deepest thoughts go his wife, Nina, of whom he spoke so often and so fondly, and his family.

I’m writing this in English, because, well, this seems only fitting and more natural to me at this moment. I had the luck of meeting him through my translator work at Imaginales, where I have been blessed to accompany for a few days legends of the field – and, for reasons that will never be clear to me but for which I am profoundly grateful, he took a liking to me, and we started exchanging beyond his journeys to France, developing what I hope I can call a friendship.

This, in a nutshell, will tell you who Chris was: this giant of a man (both physically – he was tall! – and culturally, with such a refined, successful career) took a genuine, caring interest in the random guy allocated to him for just a few days. He was such a gentle, discreet presence – and yet so funny, of course, so witty in that English way I’ve always admired. Having dinner with him was always to promise of lots of laughs, sudden deep questions about art and life, and funny, biting anecdotes about the Golden Age of SF. We discovered we had a common love for Australia and Scotland, and a common hatred for Brexit.

When you learn that you will be following such a legend as Christopher Priest, you are of course quite anxious to do your job right, and to do service to anything that he says – because you are, in essence, his voice for the French audience. I will always remember – and cherish, among other things – the first time we met; I was quaking a little inside, put on my most professional face of course, and said something inane along the lines of « Hello, I am Lionel, I will be your translator, are you Christopher Priest? » He immediately answered: « Yes, but do not call Christopher. That’s too formal. If you’re my translator, you call me Chris. »

I still cannot believe that he treated me as an equal, that I got to speak and joke with him – and he may possibly be quite irritated at me to read me speak so highly of him, as he was always so humble and disregarding of honors; but again, I am so grateful to have been able to know him a little. There is a whole section in Comment écrire de la fiction ? that I owe to talking with him, to benefitting from his vast experience simply through our talks – near the end of the book, about the fact that your judgment on your writing will always move faster than your skill, leading to potential despair. As I was skirting burn-out, and I kind of whined about it in our correspondence, he never judged, but instead led me, with humility, to understand and grasp this vital lesson for myself. This is how kind and masterful he was.

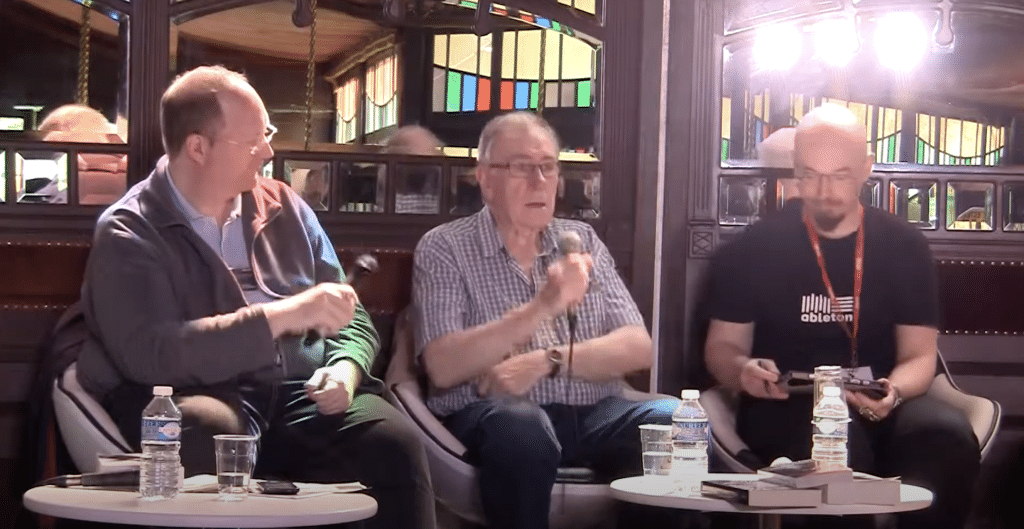

He loved to tease me during our panels together and find the most wacky things to say, or even do on stage, to have me translate or imitate. There’s a story he often told around The Prestige, about a magician who would spend his whole life walking stooped like a very old man so that nobody could ever guess that he could actually walk upright, which allowed him to produce on stage, from under his clothes, a huge fishbowl seemingly out of thin air. He would show the struggling gait to the audience; and then be adamant that I « translate » it, which of course I was only delighted to do. I remember fondly the twinkle in his eye as we played that unspoken game, as I answered his tricks and traps with some of mine.

There was another panel where, to make things interesting, he said among a bunch of fantasy writers that good books should never come with maps (actually making very good points about how the words themselves should produce the sense of space, landscape and exploration). After the panel, I showed him smiling the maps in my own books – he was immediately so embarrassed, thinking he had been insensitive to me; that’s how gentle he was. Of course, he had not been – he did raise some excellent points about maps – and this became a long-standing joke.

Not long enough, I’m afraid, even more as I’m a terrible correspondent (as some of you here might know) and started about every email with apologies as to why I had not written for the past three months (as some of you here might also know).

I am not sure he would like me to feel so terribly sad as I am now, feeling I have missed so much. I try my very best to feel grateful and fortunate instead. Thank you, Chris, for giving me the wondrous gift of your friendship. And for giving me your most precious advice:

The secret of a good book is NO BLOODY MAPS.

Oui je l’avais rencontré pendant un congrès Boréal et nous avions parlé 3 à 4 heures. Je l’avais trouvé humble et très humain. Curieux de mon parcours même si je n’écris pas. Cultivé et inquiet du Brexit. Un beau souvenir